Adam Busiakiewicz

Report by Derek Latham

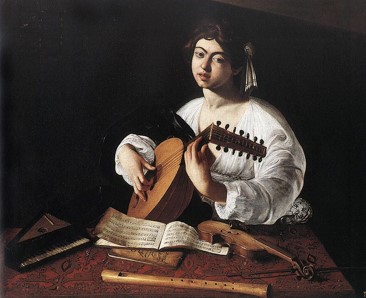

Caravaggio The Lute Player, 1596,

oil on canvas, 100cm x 126.5 cm,

The Wildenstein Collection

By way of introduction to his talk at the Arts Society Scarborough meeting on February 19th Mr Adam Busiakiewicz played three short dances – possibly the first time some of us had consciously listened to the sweet notes of the lute as a solo instrument. Adam explained that in the 16th and 17th centuries the lute was pre-eminent among musical instruments, and consequently featured prominently in paintings of the time, perhaps the best known example being “The Lute Player” by Caravaggio. Holbein painted the instrument many times, sometimes as a still life subject, and at other times in a painting of a social gathering. One example we were shown was at the court of Henry VIII, who, it was said, owned twenty six of the instruments at the time of his death. Henry’s daughter Elizabeth also played the lute. Titian also favoured the instrument and one of his oft-repeated subjects was Venus and the lute player. Also mentioned by Adam was the late 15th century German painter Albrecht Duerer and his woodcut of a lute in the process of manufacture. Painters in the renaissance period were often skilled also in musicianship, and the lute was their favoured instrument. The polymath Leonardo da Vinci in particular was a highly talented player. The lute was the “queen” of instruments, Adam pointed out, but the “king” was always the human voice.

After receiving a Bachelor’s Degree in History from University College, London, Adam Busiakiewicz held a curatorial role at Warwick Castle. Supported by an AHRC Studentship, he completed a Master’s Degree in Fine and Decorative Art at the Sotheby’s Institute. He has since worked at several London auction houses and still works as a freelance researcher for various art dealers. In 2014 he became the youngest guide lecturer at the Wallace Collection, and has since become an accredited lecturer for the Arts Society. He has given lectures, courses and workshops at the National Gallery and Victoria and Albert Museum. In 2017 he was the editor of the Georgian Group’s 80th Anniversary exhibition catalogue, entitled Splendour! Art in Living Craftsmanship (2017). He is currently pursuing a doctorate in Art History at the University of Warwick.

The lute was developed in the Middle East in the distant past (the name comes from the Arabic word for “the wood”), and it was imported into Europe from the late 13th century onwards. From the early instruments which were purely functional it became an opportunity for European craftsmen and jewellers to show their decorative skills; Adam showed images of lutes adorned with ivory and with gilded brass. Some were so highly decorated that they were primarily show-pieces; they were objects of beauty – not to be played. Players of early lutes used a feather plectrum but in the 16th century it became the practice to pluck the strings with the fingers. The lute, we were told, always sounds best in a small room with hard surfaces. Soft furnishings mute the delicate tones of the instrument. As well as being a classical guitarist for which he was best known Julian Bream was a highly accomplished lutenist and was named by Adam as the foremost lutenist of recent years. Adam likened the music of the lute to the singing of the counter tenor voice, citing especially that of the Englishman Alfred Deller, although he expressed relief that today’s singers do not have to undergo the physical deprivations of 16th century castrati.

Adam then played a piece by the early 17th century English composer and lutenist John Dowland. Melancholy, Adam told us, was “in fashion” at that time, and Dowland wrote much melancholic music which he played during his frequent travels throughout Europe. “Flow my tears” and “Come, heavy sleep” were hit numbers. Adam showed a portrait of another renowned lutenist, Nicholas Lanier, Master of the King’s Musick to Charles I, to underline the ubiquitous presence of the lute in the music scene of the 15th and 16th centuries and in the paintings by the old masters which bring to life those bygone days for us.

Finally, like a rabbit out of the hat, Adam produced from behind the lectern an enormous lute-like instrument, fully five feet long. This is the theorbo, and Adam ended a most enjoyable talk and musical performance with a short recital on this rare and remarkable instrument.

The Lute Player

Caravaggio, 1596, oil on canvas, 100cm x 126.5 cm,

The Wildenstein Collection